The United States is running out of time to secure its place as the first nation to return humans to the Moon in the 21st century. NASA’s official schedule remains unchanged — Artemis III, the mission intended to achieve the next crewed lunar landing, is still listed as “no earlier than mid-2027.” But that target, roughly three years ahead of China’s publicly stated 2030 goal, is becoming increasingly difficult to defend.

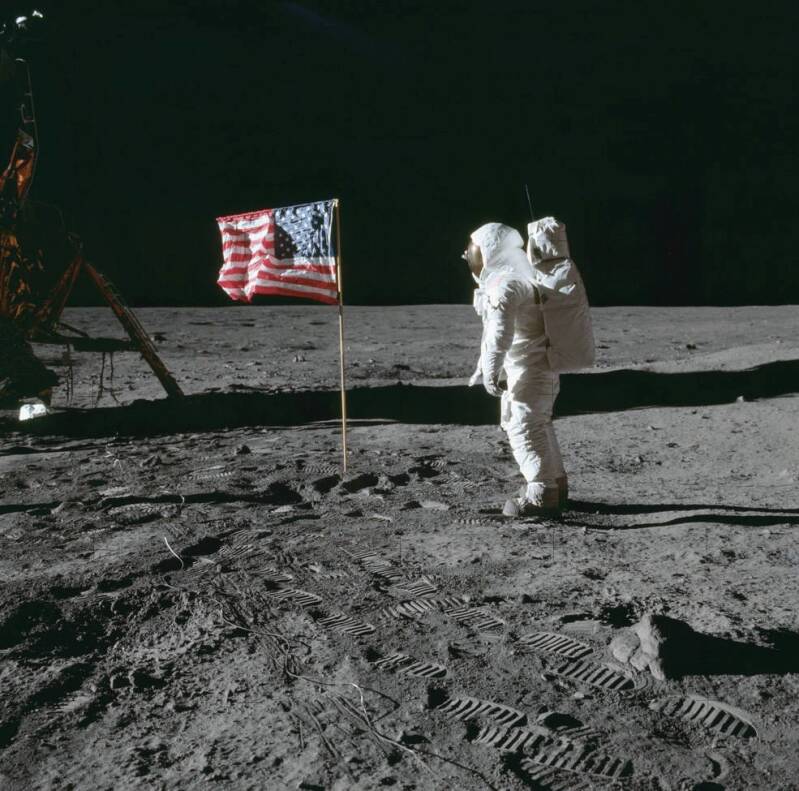

Apollo 11 astronaut Aldrin saluting the flag at Tranquility Base.

Across NASA, the sense of urgency is unmistakable. Acting Administrator Sean Duffy has said repeatedly that the United States must not allow China to land first. But while Washington speaks in terms of competition, Beijing projects calm confidence. The China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) maintains that its program is not a race, but a steady national undertaking — one it insists remains on schedule.

Which of these visions prevails may depend on whether NASA can navigate a string of complex, interdependent milestones spanning multiple vehicles, contractors and mission systems — any one of which could derail the timeline.

A Schedule Under Heavy Strain

NASA’s Artemis schedule has absorbed delay after delay. Artemis II — the first crewed Orion flight — slipped from November 2024 to September 2025, then again to April 2026. As of November 2025, the agency is working toward a launch no earlier than February 5, 2026, within a window that extends through April.

Artemis III, the mission intended to return humans to the lunar surface, is officially targeting mid-2027. But NASA leadership, outside review boards and independent analysts have all warned that this date is likely optimistic.

The Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel, which visited SpaceX’s Starbase facility in September 2025, went further: the Starship Human Landing System (HLS), they said, “could be years late.”

China, by contrast, has maintained a steady timeline. CMSA reaffirmed in March 2025 that its 2030 human lunar landing plan remains intact. Key components — the Long March 10 heavy lifter, Mengzhou crew vehicle, Lanyue lander, Wangyu lunar suit, and Tansuo rover — are all advancing through prototype development. Ground infrastructure at Wenchang is also under construction to support the missions.

Several challenges must converge perfectly for the U.S. to land on the Moon by 2027. Many of them remain unresolved.

- SpaceX Starship Refueling — The Pivotal Unknown .The largest technical risk is SpaceX’s yet-unproven orbital propellant transfer system. Starship must be refueled in Earth orbit by multiple tanker flights — possibly 8 to 16 or more — transferring hundreds of tons of cryogenic methane and oxygen. No one has ever accomplished anything comparable.

SpaceX is working toward a NASA-contracted demonstration mission, tentatively understood to be planned for mid-2026. But neither NASA nor SpaceX has publicly committed to a firm date. If this test slips, Artemis III will slip with it.

Rapid boiloff of cryogenic propellants means tanker launches must be conducted in fast succession. To meet this demand, SpaceX aims to add a second Starship launch site at Kennedy Space Center. But launching 10–20 complex missions back-to-back represents an unprecedented operational challenge.

- Starship Block 3 — A Major Redesign Still Untested

NASA is depending on SpaceX’s upcoming Block 3 Starship configuration, which features: a redesigned booster structure, expanded propellant capacity, a NASA-compliant docking system, and integrated hardware for orbital refueling.

Although SpaceX has completed over 40,000 seconds of testing on the upgraded Raptor 3 engines, Block 3 introduces major structural and mechanical changes — each a potential failure point requiring extensive flight testing. The Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel has cautioned that delays here could cascade directly into the refueling demo schedule.

- Orion Heat Shield — A Fix That Must Work. NASA has now traced Artemis I’s unexpectedly severe heat-shield erosion to trapped gases within the Avcoat ablative material during the skip-entry maneuver. To prevent recurrence, engineers are modifying the material’s permeability, attachment methods and reentry trajectory. Early tests look promising, but NASA admits that any new anomaly discovered during Artemis II preparations could impose an additional 12–24-month delay.

- Axiom’s Lunar Spacesuit —Axiom Space’s AxEMU suit — tested underwater in 2024–2025 — must clear its final development milestones and full qualification in time for Artemis III. The compressed timeline makes the suit a critical-path item, and any significant setback could delay the mission.

China’s Steadier Approach

China’s architecture avoids NASA’s biggest risk: orbital refueling. Its two-launch lunar mission design sends the Mengzhou crew capsule and Lanyue lander separately into lunar orbit atop Long March 10 rockets.

The downside: the Long March 10 has never flown. But China is progressing methodically. In August 2025, CMSA completed a full-sequence ground test of the Lanyue lander in lunar-analogue conditions. With no requirement for complex in-space refueling, China’s primary risk is concentrated in Long March 10 — a simpler dependency than NASA’s multi-system architecture.

NASA’s Backup Planning

Aware of the mounting risks, NASA has reopened lunar lander procurement. In October 2025, Duffy invited both SpaceX and Blue Origin to propose accelerated alternatives for Artemis III. Blue Origin’s Blue Moon lander — slated for Artemis V — could theoretically be adapted, though its own schedule is tight. NASA has also expanded long-term lunar infrastructure studies under the NextSTEP Appendix R program to provide additional fallback options. But the program continues to face political uncertainty. The Trump administration’s proposed 2026 “skinny budget” sought major cuts, including ending SLS and Orion after Artemis III. Congress rejected the proposal and funded SLS through 2029, but future political shifts could resurrect similar attempts.

Can the U.S. Still Land First?

The timeline leaves NASA little margin for error. Assuming Artemis II flies in early 2026, NASA would have about 18 months to execute:

- Artemis II flight and data analysis

- Starship orbital refueling demonstration

- Block 3 flight tests

- Uncrewed HLS landing demo

- Full HLS crewed variant integration

- SLS/Orion stack preparation

- Artemis III launch and lunar rendezvous

Each step carries substantial risk. Independent analysts now increasingly suggest 2028 or 2029 as the more realistic landing window. A slip into 2030 is not out of the question — which would place the U.S. and China neck-and-neck.

The immediate question is which nation lands first. But many experts argue the more consequential race is the one that follows: building a sustained lunar presence.

Here, the U.S. may hold an advantage through international partnerships and proven experience with long-duration operations. But that long game relies on clearing the urgent hurdles in the next two years.

Conclusion

The United States can still beat China back to the Moon. But doing so requires a flawless sequence of breakthroughs like successful Orion heat-shield redesign, timely spacesuit qualification, rapid Starship Block 3 progress, and a historic first-of-its-kind orbital propellant transfer. Any major delay could push Artemis III into China’s 2030 window.

The coming 18 months will determine not only who returns to the lunar surface first — but who leads humanity’s next chapter on the Moon.

Add comment

Comments